French in multilingual contexts: A student’s perspective on doing fieldwork – PART I

In this three-part series, Pierre-Loup Lenoir reflects on his journey as a student assistant conducting ethnographic research on multilingualism and French in the Netherlands.

During the first half of 2024, Pierre- Loup Lenoir worked as a student assistant as part of a research project led by Dr Naomi Truan, Assistant Professor of German Sociolinguistics at the Leiden University Centre for Linguistics (LUCL). Under the umbrella of HERLING, the research lab for the study of Heritage Languages of the Netherlands, he writes about his experiences conducting sociolinguistic fieldwork for the very first time. This is the first post as part of a three-part series.

A brief introduction

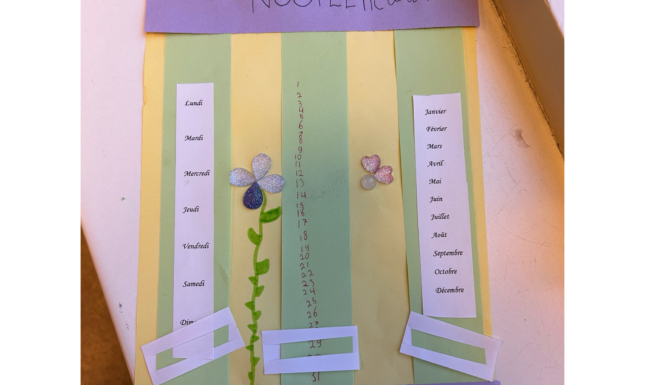

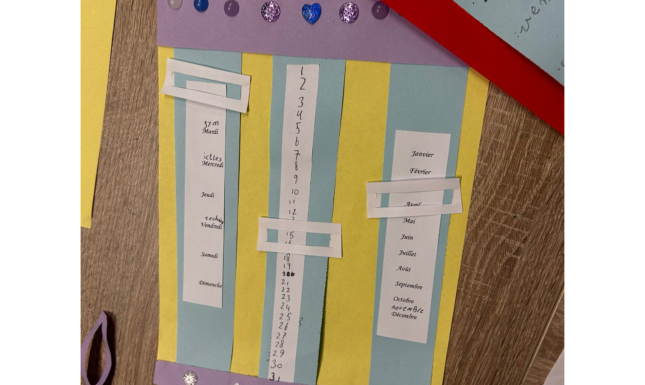

“Je parle aussi français! Ik spreek ook Frans!” is a project initiated by the French Institute in the Netherlands, in which HERLING acts as a scientific partner. Based on weekly after-school workshops taking place in Rotterdam (Crooswijk) and The Hague (Bouwlust en Vrederust), the project seeks to develop the knowledge of French for children aged 6 to 11 through a valorisation of their cultural and linguistic heritage.

So far, the project has focused on Dutch children with a Moroccan migration background, under the assumption that they may be either French-speaking or connected to a French-speaking family heritage. Being a first speaker of French and a French citizen living in the Netherlands, with a background in education, I was very curious about how French would be transmitted as an extracurricular activity. My responsibilities included consistent data collection and transcription activities, looking at how the children interact during the workshops and why teachers and parents are interested in the project.

A change of plans

As part of our collaboration with the French Institute, I regularly attended activity-based language workshops led by teachers of the Alliance Française of Rotterdam and of The Hague, which took place after-school in local community centres. A few initial expectations, built from preparatory meetings and email exchanges, guided our approach and methodology:

- The workshops, conducted in French, help children mobilize and develop their knowledge of French (baseline: children are passive speakers of French, which means they had enough exposure to French in childhood / prior to the workshops to understand French very well, but may have only little or no active command of French).

- Alongside fieldnotes, audio and video recordings of the workshops would be possible.

- Complementary interviews with teachers and parents would be conducted in parallel to the workshops.

However, my first visits to the Rotterdam location quickly altered these initial beliefs and research objectives. The core assumption that the children involved in the workshops had French as a heritage language, based on the feedback of the French Institute, quickly proved to be unrealistic. A heritage language can be defined as “a language learned at home that is not the dominant language of the country” (Aalberse, Backus & Muysken 2019: 1). These Dutch children, of which a majority were second or third generation immigrants of Moroccan origins, lacked any observable knowledge of French. Our assumption that they would understand French, at least passively, proved hard to sustain despite some knowledge of basic vocabulary.

In other words, the French Institute’s imagined view of French as a heritage language for these children did not hold. Indeed, like any other Dutch children, the children had Dutch as a first language, sometimes Moroccan Arabic or Berber (depending on the family) as a heritage language, as well as English as a second or third language through their immersion in the Dutch school system.

A new research focus

Considering this updated view of the children’s linguistic repertoire, the research focus shifted away from heritage languages towards a study of the forms of multilingualism promoted in the workshops. Aside from having to profoundly amend our research goals and approach to the project, the initial field observations also put in question my position as a researcher: My profile as a first speaker of French had become largely irrelevant to the project, despite initially representing a key factor for my role as a student assistant. Indeed, a strong command of Dutch and/or Moroccan Arabic or Berber would have been more useful than proficiency in French. In the end my knowledge of Dutch proved to be enough to understand and follow the workshop interactions, yet remained insufficient to conduct interviews or have quick-witted conversations with the participants.

Reflections and lessons learned

As a first-time field researcher operating in unknown territory, these initial setbacks took some time to digest, most notably towards my own positionality and legitimacy towards the project. The loosely shaped workshops and the large age range made it a difficult environment for an external observer to navigate: The activity-based teaching of French entailed spontaneous exchanges between teachers and children as well as children to children. Keeping up linguistically with the effective multilingualism of the children (also a struggle for the teachers) proved to be a challenge at first but I became more confident with each visit.

Here, the possibility of audio and video recordings to act as a safety net would have allowed me to look back and notice details that I may have not noticed during the observation. Initially planned for, recordings did not take place due to the practical difficulties experienced by our collaborators in gathering the consent of each participant. These recordings would have also allowed me to focus more specifically on data easy to miss if not recorded, for instance side conversations between the children I was not a part of. Despite the added pressure to ensure precise observations and consistent notetaking without complementary recordings, I managed to extract relevant data from my field notes by compromising for a more selective approach both in my active listening and my notetaking.

In conclusion, this project may not only be about my discovery of fieldwork but may also show the difficulties of conducting research as part of a temporally restricted student assistant role. At first I was confident in my ability to successfully collect data over the span of a six-month period, but quickly realized much more time was needed to properly set-up a positive research environment. The lack of consideration for my temporality led to an incomplete data collection, which in turn prevented any meaningful findings. I am now able to understand what it takes to conduct research from start to finish, which will prove to be highly valuable for my Master research projects.

In my next blog post, I will further explore the sensitive context of our collaborative research.

If you would like to learn more about the project, please reach out to Dr Naomi Truan.

Reference

Aalberse, Suzanne, Albert Backus & Pieter Muysken. 2019. Heritage Languages: A language contact approach (Studies in Bilingualism). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/sibil.58.